|

No one was looking when West Berry Street died.

Berry's death was slow and subtle, and for a long time the street's condition was easier to ignore than to address. That attitude was evident at TCU, where for years admissions materials didn't mark Berry Street on maps for visitors. Instead, prospective students were offered more circuitous paths to University Drive and Hulen Street and away from the corroded south Fort Worth artery.

But it gradually became clear to TCU leaders that even if the neighborhood's decline was somebody else's fault, it was everybody's problem. The trappings of urban decay -- vacant storefronts, substandard housing, rising crime -- were on the eastern fringe of the campus, forcing the university to make a choice.

"We could provide a safe campus by putting up fences and really retreating into ourselves, or we could become more a part of the community and help the community rid itself of some of the eyesores and behavior we didn't like," said Don Mills '72 (MDiv), TCU's vice chancellor for student affairs. "We could provide a safe campus by putting up fences and really retreating into ourselves, or we could become more a part of the community and help the community rid itself of some of the eyesores and behavior we didn't like," said Don Mills '72 (MDiv), TCU's vice chancellor for student affairs.

In the mid-1990s a TCU contingent led by Mills and then-Chancellor William H. Tucker '56 joined with a group of Berry Street stakeholders who had decided it was time to roll up their sleeves and fix the place.

A little more than a decade later, a new West Berry is coming into focus. The neighborhood is starting to resemble the urban village that TCU and city leaders desire.

West Berry's reemergence is a story of partnership. By working toward a common cause, TCU, Fort Worth, businesses and nearby residents have redefined an area once left for dead. It is a success story in which everyone involved is both a beneficiary and a contributor.

A street is born

Long before West Berry's mid-century heyday -- when it was home to Cox's department store, Kings Liquor and the Hi-Hat Lounge -- the street was little more than a country lane. TCU's arrival in 1910 was central to Berry's becoming in the 1940s a bustling traffic conduit and business hub.

When the University settled into its current surroundings in 1911, the campus was a sparse 56 acres on the city's periphery. As an enticement to make Fort Worth home, city fathers agreed to extend utilities and the streetcar line to the campus.

"For years after, that was the boondocks," said historian Rick Selcer '80 (PhD), a Fort Worth native and author of several books on the settling of the city. "Fort Worth police didn't patrol. It wasn't considered in their jurisdiction. That's how empty it was between downtown and TCU."

As early as the mid-1920s, though, civic leaders foresaw Berry Street's potential. For the street, then a dirt-and-gravel surface, to develop as a commercial corridor connecting the campus to Fort Worth's south side, it would need to be widened and paved.

"We could provide a safe campus by putting up fences and really retreating into ourselves, or we could become more a part of the community and help the community rid itself of some of the eyesores and behavior we didn't like."

Don Mills '72 (MDiv)

vice chancellor for student affiars |

In 1926 the Fort Worth City Council, at the behest of City Manager O.E. Carr, approved upgrading Berry from Forest Park Boulevard near TCU east to the city limits near Hemphill Street. In a Fort Worth Star-Telegram story dated Oct. 12, 1926, Carr hails this as "the most important street project discussed in Fort Worth in six months."

At a time when modernity was rapidly overhauling the Cowtown landscape, six months must have seemed like an eternity to the forward-thinking administrator. The newspaper went on: "Carr explained that Berry Street, when widened and improved, would give territory in the vicinity a 'straight shoot' to T.C.U. and predicted that it would eventually become one of the best business streets in the city."

That first improvement project widened the road to 100 feet -- 54 feet of roadway with the rest set aside "for ample side parking spaces." The street was now brick on top of concrete. As Fort Worth residents sipped their morning coffee April 1, 1930, the last bricks were laid. A Star-Telegram story that morning announced, "Berry Street is now the only paved thoroughfare linking directly the South Side and T.C.U."

'A busy, active, alive street'

By the 1950s, Berry had become the destination Carr envisioned. David Murph '75 (PhD), TCU's director of church relations and author of Before Texas Changed, remembers the West Berry of his youth, when it was the place to shop for anything families living near the university could want or need.

From University State Bank to Skillern's Drugstore to Cox's, the storefronts buzzed with activity, especially on Saturdays, when pedestrians strolled to and from the street's many businesses. When it was time to buy shoes, Murph joined other Berry Street patrons at Mehl's Shoeland. For clothing, it was Cox's; for sporting goods, Beyette's Hobby Store; for a hearty meal, Colonial Cafeteria.

"People did most of their living and shopping on Berry Street," said Murph, who lived on Boyd Street near campus and attended Paschal High School. "It's very hard for people who only know Berry Street from the 1970s and 1980s on to really have a good idea of what it was like. Berry was a very active commercial thoroughfare from University Drive up to Eighth Avenue." "People did most of their living and shopping on Berry Street," said Murph, who lived on Boyd Street near campus and attended Paschal High School. "It's very hard for people who only know Berry Street from the 1970s and 1980s on to really have a good idea of what it was like. Berry was a very active commercial thoroughfare from University Drive up to Eighth Avenue."

For TCU students, the businesses on Berry Street and parts of University Drive were not just the most popular hangouts in the 1950s and '60s -- they were about the only places to go. Bluebonnet Circle, just south of TCU down University Drive, was at the city limits. Other parts of town were not an option for the many students who didn't own cars.

"It was a busy, active, alive street," Selcer said. "When the day businesses weren't open, it became a main drag, and it was safe."

West Berry provided an assortment of restaurants and hangouts. El Chico Mexican restaurant and Carshon's Delicatessen (now on Cleburne Road) shared the streetscape with the Hi-Hat and The House of Pizza (or The HOP) and the gimmicky Merry-go-Round, which served up cheap burgers and a kitschy atmosphere.

"Berry Street was an important part of the TCU community," Jerre Todd '57 said. "It was the entrance to TCU by the south."

Todd knows firsthand the fun TCU students had on Berry. In the mid-1960s he ran his public relations firm from an old house at Berry Street and Cockrell Avenue. The office was across from the Hi-Hat, and Todd recalls how students would sometimes have one soda pop too many and have trouble navigating the establishment's steep stairs.

"So the owner would let them sleep there," Todd said. "In the morning you'd see them coming up the steps.

Berry's decline

Fernando Costa, Fort Worth's director of planning and development, understands what makes an urban neighborhood succeed or fail. Before becoming the city's planning director in 1998, he served in the same capacity in Atlanta. The 1996 Summer Olympics provided the momentum he needed to jump-start the renewal of blighted areas in the Georgia capital's inner city.

“I think 30 or more years ago, we lacked a good understanding about the importance of

preserving the strong central city neighborhoods and

commercial districts.”

Fernando Costa

Fort Worth Director of Planning and Development |

"We were able to promote the development of downtown housing and bring vitality to neighborhoods that had been neglected over the years," he said. "The result is that Atlanta is experiencing a dramatic reversal." In Texas, Costa found many of the same bad signs. A neighborhood's vitality, he says, links to larger social trends that may not be obvious to people going about their daily lives.

In West Berry's case, changing traffic and living patterns in the 1970s sped the deterioration. People were abandoning central city neighborhoods for the suburbs. Fort Worth, today one of the fastest growing big cities in the country, was declining in population 30 years ago.

"I think 30 or more years ago, we lacked a good understanding about the importance of preserving the strong central city neighborhoods and commercial districts," Costa said.

Another contributor to Berry's downfall was the arrival of enclosed shopping malls. Seminary South, one of the first regional malls in the country, opened in the 1960s, and a decade later Hulen Mall became the preferred one-stop-shopping destination in south Fort Worth.

"The malls changed everything: the way we shopped, the way we traveled," Murph said. "Things changed dramatically."

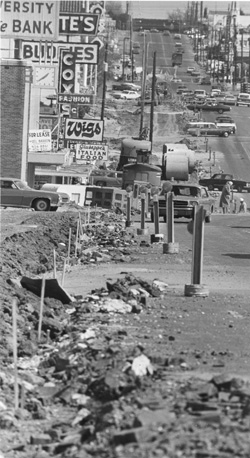

The West Berry area's final blow was poor city planning. City leaders in the 1970s were primarily concerned with traffic, particularly how to move it rapidly through what they identified as the city's major thoroughfares. Berry -- considered the main route connecting the older south side neighborhoods to the new Hulen Street -- was widened and redesigned in a way that discouraged stopping and shopping. As a result, business declined. The neighborhood's appearance followed suit.

Kenneth Barr '64, Fort Worth mayor from 1996 to 2003, prefers to think that whatever mistakes city leaders of the 1960s and '70s made, they did so with good intentions.

"Those people were intelligent," he said. "I assume they did things for the right reason and had the interest of the city in mind. From a traffic flow perspective, it made a great deal of sense. Time would show that it was not in the best interest of Berry Street. But they were looking at it from mid-20th century eyes, and we're looking at it with 21st century eyes. Cities can change a great deal in 50 years." "Those people were intelligent," he said. "I assume they did things for the right reason and had the interest of the city in mind. From a traffic flow perspective, it made a great deal of sense. Time would show that it was not in the best interest of Berry Street. But they were looking at it from mid-20th century eyes, and we're looking at it with 21st century eyes. Cities can change a great deal in 50 years."

Whatever the city leaders were thinking, West Berry was a relic in the new urban landscape. Stripling & Cox's department store symbolized the stagnation when it closed in the mid-1990s after more than 40 years as West Berry's retail anchor.

"That was the bottoming-out point," Barr said. "When Cox's moved out, there weren't any anchors left."

But some good may have come from Cox's demise.

"That decision sounded an alarm for leaders of the surrounding neighborhoods," Costa said. "They finally came to see that the time had come to do something about the decline of Berry Street because the street was no longer a great asset for the neighborhood or for the city."

Confronting the problem

Chancellor Emeritus Tucker has always considered TCU's location an advantage. Attractive features border the campus in almost every direction. Head south on University Drive from Interstate 30 and note the upscale retailers in University Park Village, then the picturesque Trinity River and the rustic Log Cabin Village. Hang a right at Colonial Parkway and you're treated to views of stately homes and Colonial Country Club. Or turn left into the internationally recognized Fort Worth Zoo. Similar superlatives can be used to describe the Hulen Street-Bellaire Drive area on the western edge of campus.

“They did things for the right reason and had the interest of the city in mind. From a traffic flow perspective, it made a great deal of sense. Time would show that it was not in the best interest of Berry Street. But they were looking at it from mid-20th century eyes, and we're looking at it with 21st century eyes. Cities can change a great deal in 50 years.”

Ken Barr '64

former Fort Worth mayor and councilman |

"Coming to TCU from any major artery, you run into a nice environment," said Tucker, TCU's top administrator from 1979 to 1998. "The surrounding area, the ambience beyond the campus, was attractive -- made more so because of the revitalization of University Drive from I-30 down University to campus. That whole shopping area was a wonderful upgrade of University Drive."

Every route to campus was aesthetically pleasing, except one.

"One area was in bad shape, and that was coming off the interstate [I-35] down Berry Street to get to the TCU campus," Tucker said. "That area was not only in bad shape but declining."

At the same time that TCU leaders were discussing what to do about Berry Street, Barr, then a city councilman, was organizing a town hall meeting of stakeholders. In November 1995 a small group of business owners and residents met to discuss the neighborhood's deterioration. In attendance that night were Tucker and Mills.

The gathering was the first in a series of meetings that led to the founding in 1996 of the Berry Street Initiative, a citizens group that would work closely with the city to develop public and private revitalization goals. It also was a signal that TCU intended to assume an active role in cleaning up the street.

The university's focus centered on the fading areas on and around the north side of West Berry.

"We couldn't take on the world," Tucker said, "so we took on the north side."

A significant player

Where Leibrock Village, a housing complex for Brite Divinity School students, stands on McCart Avenue just north of Berry, in the mid-1990s there was a rundown apartment complex.

Besides being unattractive, it was a safety risk. Drug dealings and robberies were not uncommon there. Tucker invited Barr to ride in his car past the apartments and other unsightly features on Berry and its side streets. Besides being unattractive, it was a safety risk. Drug dealings and robberies were not uncommon there. Tucker invited Barr to ride in his car past the apartments and other unsightly features on Berry and its side streets.

"When we got to that whole complex of substandard housing on McCart, there was graffiti everywhere," Tucker recalled. "He understood what we wanted to do. As a consequence, things started to fall in place."

TCU began acquiring parcels of land contiguous to campus and tearing down unattractive structures. The McCart apartments were razed and Brite and TCU graduate housing built. The university also bought other properties along and near Berry, turning some of them into parking lots or offices.

"We benefit from Fort Worth, so TCU needs to be a significant player in growing and enhancing the quality of life of this city," Tucker said. "And it really made sense to do this because it was the one area around our campus that was blighted."

TCU's most important property acquisition was probably the old Safeway building in 1997. The university, which needed a bookstore larger than the modest space the Brown-Lupton Student Center could provide, partnered with Barnes & Noble to turn the former grocery into a spacious stand-alone bookstore.

The TCU Barnes & Noble bookstore, which opened in fall 1997, served the students' needs as well as provided a retail destination for the public. The vibrant structure, with its signature clock tower facing Berry Street at University Drive like a sentinel, came to signify the beginning of West Berry's renewal.

"When the store opened, I remember what a wonderful day it was for me," Tucker said. "We were simultaneously acquiring properties, but that was the first symbol."

Taking initiative

Kubes Jewelers has been on Berry Street for more than 50 years. The family-owned business founded by Joseph E. Kubes Sr. has a loyal customer base that includes many in the TCU community.

“We benefit from Fort Worth, so TCU needs to be a significant player in growing and enhancing the quality of life of this city.”

William H. Tucker '56

chancellor emeritus |

"When I was a student in the '50s, I shopped -- I guess that would be an exaggeration -- I looked at Kubes," Tucker said.

The West Berry mainstay, though, was on the verge of leaving by the mid-1990s. Co-owner Rick Kubes, the founder's son, cites a "vacuum of leadership" then plaguing Berry Street. So many of the stores, including Mehl's Shoeland, Colonial Cafeteria and Cox's, were gone. Kubes and his family wondered if maybe it was time to go, too.

But could other options, like opening a free-standing location at University Park Village, match the cozy atmosphere that their customer base loved about the Berry Street store? And moving out would be another blow for the down-on-its-luck neighborhood.

"We've literally been on this block 50 years, and like long-term investors we knew it was going to have its ups and downs," Rick Kubes said. "If we left, it would be just another negative effect on this area."

Even with no indications that things were improving, Kubes joined the Berry Street Initiative. He would prove to be a vital cog in its early struggle to recruit members.

Apathy plagued Berry's business community, in part due to the number of chain retailers lacking deep roots in the area. So members of the initiative approached the nearby neighborhood associations for help.

The neighbors, like current Berry Street Initiative president Sandra Dennehy, were the customers who shopped at Berry's stores and, ultimately, the ones who had the most to gain from West Berry's vitality.

"I love Fort Worth," Dennehy says. "I was raised here. I've lived here all my life. And I love the vibrancy of an urban neighborhood and an urban setting more than a suburban neighborhood."

When Berry's biggest neighbor, TCU, opened the new bookstore, the initiative had an example to show of what the neighborhood could become. On the heels of the bookstore's opening, the initiative began to make its voice heard at City Hall. In 1998 the city approved hiring a consultant to figure how to revamp the street and surrounding business district.

Slowly, things were getting better. A sign of the new optimism was the Kubes family buying the building they had long leased at Berry Street and Merida Avenue. Kubes Jewelers, for one, was there to stay.

An emerging urban village

Planning director Costa believed it would take more than cosmetics to return West Berry to top form. The neighborhood itself would need to be reimagined. He envisioned a Berry Street urban village. Planning director Costa believed it would take more than cosmetics to return West Berry to top form. The neighborhood itself would need to be reimagined. He envisioned a Berry Street urban village.

"We wanted to revitalize that part of Fort Worth by creating an economically viable place with a mix of land uses and an environment that fosters pedestrian activity and human interaction," he said.

The city took a three-pronged approach: street improvements, development incentives and mixed-use zoning.

The street work was slow to begin, frustrating some Berry denizens who wondered if it was all an empty promise. Then improvements accelerated in 2006, when funding from multiple sources, including the city, state and the North Central Texas Council of Governments (TCU also contributed to the public enhancements), became available.

From Forest Park Boulevard to Waits Avenue, the street has been repaved and narrowed from a vehicle-oriented six-lane roadway into a more foot-traffic-friendly, four-lane surface with medians and on-street parallel parking. Brick crosswalks were installed at intersections from Forest Park to Waits Avenue. Aesthetic enhancements have been added to the wider sidewalks, including benches, trash bins, lampposts, potted plants and trees. The improvements are scheduled to extend from Waits to University Drive soon.

In addition to providing capital improvements, the city designated West Berry a neighborhood empowerment zone. New investors in Berry Street properties are eligible for municipal tax abatements and reduced development fees. Rezoning has also opened the street up to developments that combine residential and commercial uses.

The on-campus Barnes & Noble burned in a March 2006 fire caused by a construction crew working to expand the building. But a bigger and better B&N is in the works on reconfigured property that includes the old site and an adjacent parcel that once housed the TCU Theatre. Its tentative opening is spring 2008. The on-campus Barnes & Noble burned in a March 2006 fire caused by a construction crew working to expand the building. But a bigger and better B&N is in the works on reconfigured property that includes the old site and an adjacent parcel that once housed the TCU Theatre. Its tentative opening is spring 2008.

The mixed-use centerpiece of the new Berry is the GrandMarc at Westberry Place, a luxurious private apartment complex for TCU students that was built on land the university owned. The multi-story facility, which opened in fall 2006, can house 600 residents and includes first-floor retail space.

"Certainly, Berry/University is a good example of an emerging urban village," Costa said. "And we attribute a large part of that success to the leadership that TCU has provided. It could not have happened without TCU's commitment to revitalizing the area."

The future of Berry

West Berry's renewal won't be complete until the south side of the street mirrors progress on the north side. For now, fast-food joints, cash loan operations, bars and tattoo parlors clutter the south side. And the neighborhood still lacks a retail destination like it had years ago with Cox's.

Most involved remain optimistic that the area will reach its full potential as a pedestrian-friendly spot for living, shopping, dining and entertainment. It takes neighborhoods a long time to fail. Coming back to life is no less gradual.

"It's not going to happen overnight," Dennehy said. "It has taken 10 years to get to this point. Anything working through the city and with funding sources you just have to be patient about."

Some are skeptical. Selcer wonders if turning Berry into an urban village with day traffic and a happening nightlife is attainable.

“It's not going to happen overnight. It has taken us 10 years to get to this point. Anything working through the city and with funding sources you just have to be patient about.”

Sandra Dennehy

Berry Street Initiative president |

"I don't know if you can create a living street just by building new buildings and pouring money into development," he said. "It's my personal opinion that living streets are based on having [destination] businesses that attract customers, not by putting in Starbucks and fancy boutiques."

On the other hand, the new-look West Berry's critical mass of consumers might be achieved by attracting the potential customers just around the corner. The neighborhood lies within walking distance of the center of the TCU campus. The location could prove to be a perfect match for the growing number of students in university housing. Freshmen and sophomores are now required to live on campus. And a $100 million construction project has brought about a Campus Commons with four residence halls (two of which opened in the fall) and a new student center, the Brown-Lupton University Union, scheduled to open in 2008.

"I think businesses will look and say, 'Wow, there's a ton of young people with money within walking distance. This will be a good place for us to be,' " Mills said.

Mills believes that good times are ahead because every phase in the development, decline and renewal of West Berry Street has occurred with the consent of the neighborhood. And the consensus now is that everyone must actively contribute to the neighborhood's vitality. Mills believes that good times are ahead because every phase in the development, decline and renewal of West Berry Street has occurred with the consent of the neighborhood. And the consensus now is that everyone must actively contribute to the neighborhood's vitality.

"If every citizen or corporate citizen decides that's somebody else's job, then nothing good happens," he said. "I think that what's made communities great all over the country is that people say, 'There are things we can do when we join together to make things better for everybody.' "

It took the residents, the businesses, the city and the university to bring a once-dead neighborhood back to life.

And it will take them all working together to keep it alive.

Comment at tcumagazine@tcu.edu.

|